No. 1

THE RED LETTER

In the 18th century, the idea that witchcraft had the power to supernaturally cause change or cause harm was not so farfetched. People at that time held strongly to their superstitious beliefs born of their ancient tales and folklore. Certainly you can picture it if you close your eyes, the strongly pointed finger and the angrily spouted accusation.. “WITCH!”. It was quite easy to be labeled as a “witch” or a “sorcerer” if you were at the center of something that could not be quickly or easily rationalized. So, in the spirit of bearing labels that are unfairly and forcibly given, let us turn to the history of the witch trials of Abiquiú where one could be labeled as more than just a witch..

STATEMENT

This piece, in keeping with the spirit of this project, is intended to be a form of exploration into the cultural identity of both my family lineage and that of the generational people of New Mexico, with a primary focus on revealing and reflecting on the hidden Indigenous bloodlines and identities within “Hispanic” communities. Although this project explores a particular part of New Mexico history, with an emphasis on the Genízaro people and identity, it is my intention to acknowledge the history and identity of all Mestizo people and lineages. I want my audience to be aware that this work unapologetically confronts and highlights the history of colonialism, social class systems, racism and internalized racism within our own communities.

ABOUT

Of the three central themes surrounding this project, “The Red Letter” primarily focus’s on that of cultural identity. It is meant to be a piece steeped in symbolism that explores the tumultuous history of identity and the “hidden” identity within the generational communities of New Mexico. This comes from my own personal experiences and upbringing in my small rural community in the Rio Chama Valley where it has often come up in conversation, the question of “what are we?” or “how do we identify?”. Needless to say, it has been the subject of much debate within my family over the years but the most common responses are always about what we are “NOT”. I have found this to be a sort of defense mechanism that has been inherited from the colonial era in which people were made to believe they would be in better positions and social standing if they shed or denounced their mixed identities, creating and perpetuating a cycle of internalized racism. This was only later enforced during the time of government sanctioned assimilation tactics and laws perpetrated against the Native American peoples of this land. In order to avoid the brutal separation of children from their families, who were then sent away to boarding schools, many Mestizo and Genízaro people would shed that identity in fear of being targeted by these cruel policies. Although this subject was usually one that was reluctantly spoken about by many modern day New Mexican families, it was my paternal grandmother who would break the silence and openly talk about our indigenous ancestry through her maternal line… A line that came from Abiquiú and the neighboring village of Barranco.

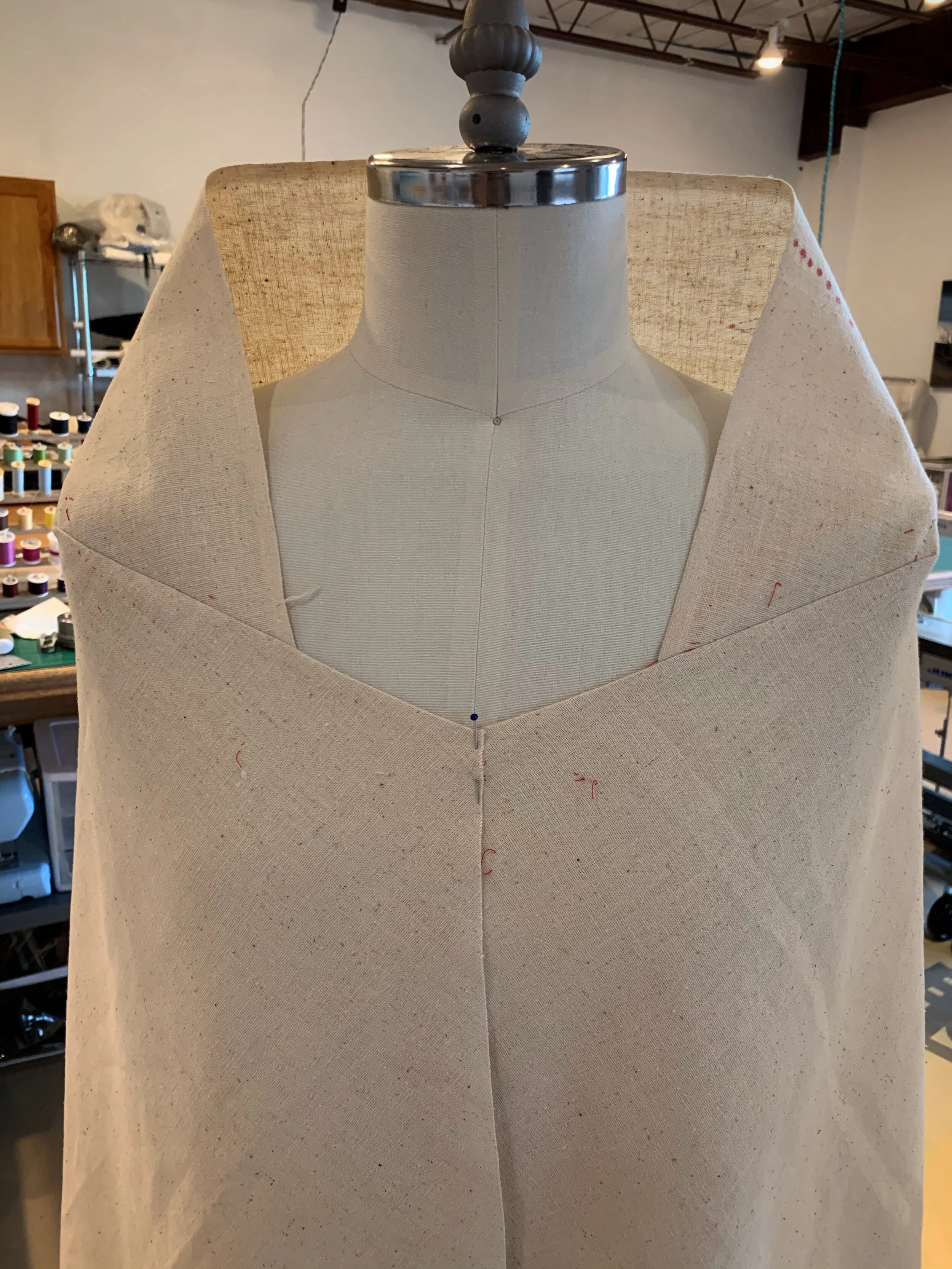

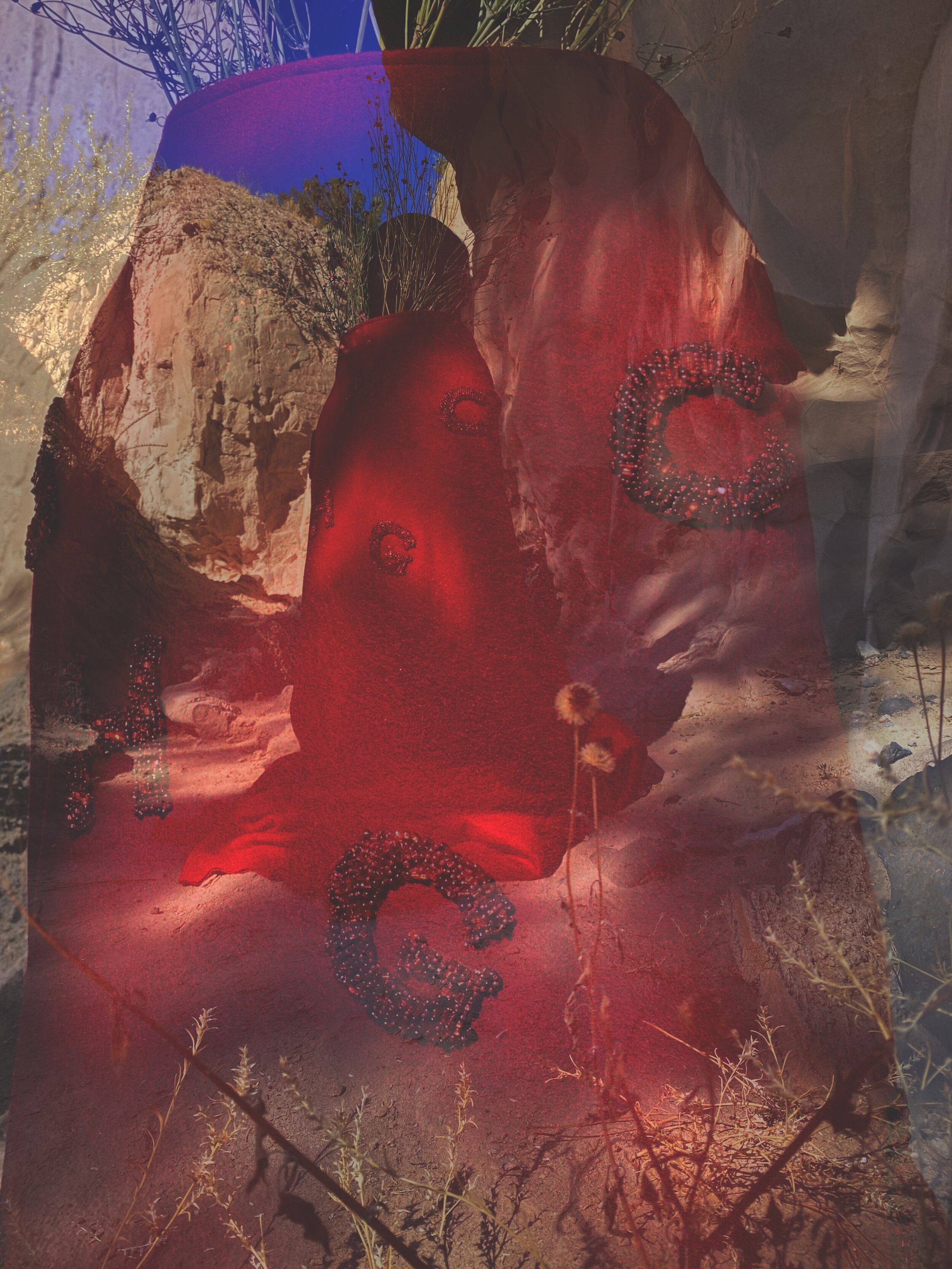

“The Red Letter” is composed of a red dyed wool fabric cut out of a single panel and patterned to mimic a traditional woven blanket that would be draped and folded over the body giving it a stiff high collar. It is embellished with several glass bead embroidered letters. The red glass beads are of various hues and sizes giving each piece a unique depth and texture. It's cut straight down the center where it can be fastened with the 5 sets of hand braided cotton cords that are attached along the center seam.

“CASTA”

“The Red Letter” is loosely inspired by Nathaniel Hawthorn’s book, “The Scarlet Letter”, wherein puritan colonists who are found to be in breach of their deeply moral religious laws are branded as sinners and in a literal sense “branded” by being made to wear a scarlet colored letter upon their clothing, representing the sin of which they are found guilty. My idea for this piece was to reinterpret that of the scarlet letter in order to reflect the use of the racist caste (or Spanish “Casta”) system, in which individuals of non European decent, primarily the indigenous peoples of this land, were labeled, categorized, and placed into a social class system. The majority of these castes were created and used to identify mixed race people or those of the mix between the Indigenous peoples and Spanish colonists. For example “Mestizo” refers to a person who is mixed with the blood of the Spanish and Indigenous people and “Genízaro”, which is a much more specific term, would eventually apply to mixed blood individuals but was originally used as a broad term to describe the many different tribal and pueblo captives and slaves serving in Spanish households; “Genízaro” is the Spanish form of the Turkish word for “janissary”, intended to mean new recruit.

The red letters scattered across this red wool cape are meant to represent a certain caste or label that would have been commonly used in colonial era New Mexico, some of which are re-emerging in contemporary society as an act of reclamation with positive new meaning. I have also chosen to create this piece intentionally bearing multiple letters as a way of symbolizing the many castes we wear as the descendants of these people. If this cape were to be worn, the wearer would quickly be made aware of the weight of the piece and naturally the bead embroidery adding to it. This is symbolic of the weight that those labels carried and the heaviness of those castes draped across the backs of our ancestors. The red throughout should come as no surprise, a symbol of blood and that of our blood ties. The use of beads is also a nod to the practice of using colored beads in folk magic that is well documented in the history of the Abiquiú trials.

For more information about these subjects please follow these links: